Curating the Beach

Weekly Excerpts #10: 07/03/2019

We have 8 days to go before the book launch of our guide. We want you to know exactly what to expect from the book and to get to know the amazing people behind this project! Every week you will be able to check in on our website in order to find a new essay, article, artist or business from the guide.

This week’s excerpt is about the artist lina klauss. liina studied Fashion-Design at the Kunsthochschule Berlin-Weissensee and has worked for fashion brands in Berlin and Tokyo. She moved to Hong Kong in 2007 and started to make environmental installations on beaches using marine litter in 2011. Her installations have been part of multiple international festivals and conferences in Europe and Asia. She collaborates with various schools, universities and corporates facilitating art-awareness-activism projects. liina is currently living in Bali, Indonesia with her family, where she works as an Artist-in-Residence at Bali Greenschool. She was chosen as a The Universal Sea Artist-in-Residence.

This week’s excerpt is about the artist lina klauss. liina studied Fashion-Design at the Kunsthochschule Berlin-Weissensee and has worked for fashion brands in Berlin and Tokyo. She moved to Hong Kong in 2007 and started to make environmental installations on beaches using marine litter in 2011. Her installations have been part of multiple international festivals and conferences in Europe and Asia. She collaborates with various schools, universities and corporates facilitating art-awareness-activism projects. liina is currently living in Bali, Indonesia with her family, where she works as an Artist-in-Residence at Bali Greenschool. She was chosen as a The Universal Sea Artist-in-Residence.

Broken Dreams No.1 – About the artwork by liina klauss

Broken Dreams No.1 is a mosaic that transforms its materials from trash to treasure. Consisting of 518 broken-down pieces of plastic and natural matter, the work organizes and coordinates the fragments by shape, color and luminosity. Used in the original way they were found, nothing is manipulated in color or size. liina klauss has collected every piece on the shores of the South China Sea in Hong Kong over one year.The resulting mosaic is perceived as beautiful. In contrast, a single piece of waste by itself is considered unsightly, dirty and worthless.

Broken Dream No.1

liina explores the perception of value and waste. The found objects intrinsically stay the same, but the perception of their worth, beauty and belonging changes depending on context, location and integration into a bigger picture. She asks, At what point do these objects become beautiful? Is it waste or is it art? What is it now worth and was it worthless before?

Worth is not inherent. It is something we as humans create, yet we are mostly unaware of our power to create value. If something is cheap in monetary terms it does not mean it is cheap in environmental and social terms. We are paying a high price for plastic with our health, with inhumane working conditions, with toxins in our food, with polluted natural environments and lost cultural heritage, the list goes on and on.

Growing up in the 1980s, liina remembers clear blue water and pristine beaches playing with shells and seaweed in Italy and Greece. Thirty years later, her own children are growing up in Hong Kong and Bali and are playing with discarded straws and bottle caps. Single-use plastics are polluting both the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean. In only one generation the environmental situation has changed dramatically.

On a material level, humans measure success by realizing their materialistic dreams. Plastic is the substance of these dreams. With plastics, we have created an avalanche of commodities. Are we happy now? The dream breaks again and again.

Curating the Beach – Essay by liina klauss

Art makes you perceive the unknown as known, the familiar as strange. It is like walking in someone else’s shoes, like looking at the world through someone else’s eyes. Art changes perception and inspires change.

In 2014 I put up a hawker stall in Hong Kong. These ‘dai pai dong’ are a common sight on Hong Kong’s streets, typically painted green and crammed to the rim with ‘stuff’ to buy. Situated on Stanley’s waterfront promenade, right between the ocean and a shopping mall, my stall is filled with colours from top to bottom. It looks like a beautiful rainbow. What is for sale there? People approach with a mindset of being able to purchase, to possess.

Jaws drop when these ‘customers’ realise that the items they are adoring are all marine litter:

Lighters, plastic bottles, buoys, broken toys, driftwood, plastic straws and shells all retrieved from a single beach in Hong Kong during only one beach-clean.

Each of the found objects is labeled with a price tag, which does not state a number in dollars but concepts like ‘awareness’ or ‘responsibility’. I am ‘selling’ single objects to visitors, complete with my signature, in exchange for the visitor’s own interpretation of these concepts. I received everything from drawings, to poems, to complete manuals how to build a boat from marine litter.

lost’n’found is an intervention in the ordinary shopping experience, questioning what we worship and what we value in our current consumerist society.

Art is the trigger that changes perspective. Changing perspective is the first and most fundamental step towards innovation.

We have been looking at the world through the lens of economic growth and monetary profit since the start of industrialisation. After 150 years of mass production it is becoming increasingly obvious that these practices do not work: global warming, acidification of the oceans, plastic gyres, death of coral reefs, overfishing, the list goes on. From the outside a healthy ocean looks the same as a dead ocean. The surface stays the same. But life itself on this planet cannot be sustained without healthy oceans.

How can we make the unseen seen? How can I as an artist make people look at what they want to avert their gaze from?

Again my answer is art. Curating the beach makes the apocalypse look like  a rainbow. It makes the ugly truth of marine pollution look beautiful. Once you look it is too late: beauty

a rainbow. It makes the ugly truth of marine pollution look beautiful. Once you look it is too late: beauty

has already captured you in its net. Advertising is using the same technique. In contrast to an advertisement, I don’t want to sell you ‘stuff’. I want to sell you awareness; all change, all innovation starts with awareness.

Curating the Beach is a process in which participants change their perception from ‘ordinary’ to ‘creative’ by looking at everything around them as if it were art. The findings on a beach range from everything that floats in the ocean to everything left behind on the beach by visitors. The biggest object we found was a refrigerator, the oddest, a pink dildo, and the oldest a 21cm diameter horse-shoe crab; a living fossil over 400 million years old.

Whatever we find, everything is art material, no discrimination made. Wherever we find ourselves, be it on a beach, on the side of a road, a river or a dump, on sand, concrete, grass or wasteland, it will be our gallery. Trash is ubiquitous. Art should be ubiquitous too. And as a consequence, awareness will be too.

The biggest object we found was a refrigerator, the oddest, a pink dildo, and the oldest a 21cm diameter horse-shoe crab; a living fossil over 400 million years old.

On a personal level, Curating the Beach is empowering as it defies the odds of being the culprit. In the face of an immeasurable amount of rubbish caused by human ignorance, it is only natural to feel sick, ashamed, helpless, depressed. This helplessness is changed into actively being part of a creative solution: You touch.

You are being touched. You see. You are a witness. You do not look away. You care. And, what might be a paradox, you are being taken care of. It is the presence of nature that heals, soothes and makes you feel being part of a bigger whole. Getting people physically out of the office or classroom, and psychologically out of their comfort zones, is as important if not more important than the result. It is as simple as being in an untouched and wild part of nature. It is using your own hands and visibly changing the environment that makes Curating the Beach so successful.

‘Curating’ comes from the Latin word ‘curare’ meaning ‘to heal’ in its active form and ‘being healed’ in its passive form. The term was first used by Judith and Richard Lang who have been curating Kehoe Beach in California since 1999. For almost two decades this couple has been combing the beach for art materials using their finds for collages of marine debris, which are turned into photographs afterwards. Curating the Beach is, visually speaking, the opposite of a beach cleanup. The effect is not making waste disappear in black rubbish bags never to be seen again. ‘Curating’ treats waste as art material and the beach like a canvas.

I have organised more than 30 of these Curating the Beach outings with corporates, schools and environmental groups. “There is no ‘away’” becomes a tangible reality when seeing a beach polluted by plastic and other man- made debris. And yet most people do not make a direct connection between marine pollution and their own daily habits. As long as we think it is ‘the other,’ as long as we keep pointing fingers, nothing will change. The human imprint cannot be ignored and we as humans cannot ignore our responsibility.

Trying to make personal responsibility more tangible, I started to do installations solely with shoes. Shoes are objects we wear directly on our bodies. Much loved pairs often carry the imprint of our feet, the imprint of our attachment, of time that passed, of memories.

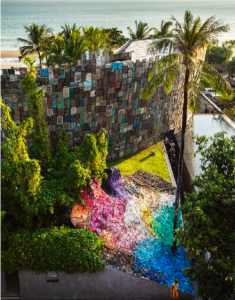

In February 2017 we started to collect flip-flops from beaches on the West coast of Bali. On our first trip with school children from Bali Greenschool we salvaged 500 ‘lost soles’ from one single beach. Other trips with One Island One Voice and EcoBali followed. By that time we had collected around 2000 single flip- flops. Lastly, highly motivated employees from Potatohead Beach Club found over 3000 more soles. All in all it took six trips and less than 100 people to collect 5000 seaborne soles on a stretch of 10km coastline. 5000 lost soles is a permanent installation at Potatohead Beach Club in Seminyak, Bali. To make the flip-flops into a permanent structure meant finding a way to join them together. Innovation Hub at Bali Greenschool produces a 100% recycled thread made from melted bottle caps. Using this thread to sew the flip-flops into a carpet-like surface took another eight weeks. The structure underneath the carpet of sandals is made from locally sourced, sustainably grown and harvested bamboo here in Bali. Ibuku, the company behind it, uses traditional methods and local craftsmen to build with bamboo. Working in a sustainable, responsible and creative manner like this is beneficial for everyone involved.

Bali is a small island and everything done here has a direct impact on the environment. It can be seen and felt directly, bad as well as good practices.

5000 salvaged shoes means literally 5000 less shoes on the streets, washing down the rivers and into the ocean every day; 5000 less shoes being burnt and polluting the air; 5000 less shoes in the earth, slowly leaking their toxins into the soil.

The challenges we face when it comes to plastic are mismanagement, durability and sheer mass. The lost soles project visually addresses mismanagement and mass. Here is a simple calculation for flip-flops in Indonesia. This footwear is commonly worn in warm climates of South-East Asia, is inexpensive and chosen by rich and poor, young and old, villagers and city-dwellers. Most flip- flops get discarded after three to four months due to material weakness. Let’s do the maths: 3.5 pairs of flipflops per person per year = seven single flip-slops. Seven flip-flops x 267 million (population of Indonesia 2018) = over 900 million discarded flip-flops in Indonesia alone. These flip-flops don’t go “away”. They are made from polyethylene foam that persists in the environment for hundreds of years without breaking down.

Working on the installation 5000 lost soles at Potatohead beach Club, 2018, Bali, Indonesia

Pete Seeger made the following statement in the 1960s, and if it was visionary back then, it is a matter of life and death today. “If it can’t be reduced, reused, repaired, rebuilt, refurbished, refinished, resold, recycled or composted, then it should be restricted, redesigned or removed from production.” Plastic is a design failure. But it is also a ‘perception’ failure. If we start looking at waste from a perspective of value instead of waste we have a resource that is cheap (money), ubiquitous (place) and abundant (mass). As a global community of designers, manufacturers, retailers, consumers and waste managers we need to move from a linear economy to a circular economy.

At this point in the industrial age, humans have already removed an excessive amount of resources from the earth. Fossil fuels and the plastics derived from fossil fuels are only one example. While still locked in this linear system we are left with an excruciating amount of what is perceived as waste.

Looking at this waste from a perspective of a circular economy, it is a resource. I want to mention two examples here of how to translate ‘waste to value’ into actual projects and products.The first example rethinks the creative process in a community of learners at Bali Green school. Looking at flip-flops as a resource and harnessing the craftsmanship of local Balinese people, I developed a technique to use flip-flops as colourful tiles for mosaics. The mosaic was created with students at Bali Greens chool, both locals and expatriates, in collaboration with Kem Bali in 2018. Kem Bali is an educational center for reduction, reuse and recycling of materials within the Green school community. Kem Bali inspired students to collect flip-flops in their respective community. After washing and drying the Polyethylene soles we cut them into squares. Reducing the soles to a neutral shape seems simple but it is actually the most crucial step in creating value. Shoes are designed for a specific application and dissolving that initial application is of utter importance. Any innovation needs the ability to reshape the old, to reimagine the habitual, to reinvent the norm.

This process of reinventing the former application of the product into some‘thing’ originally new is the starting point for innovation. Once this is mastered, the rest is easy: the squares cut from oldpolyethylene soles are used to create an image much in the tradition of a mosaic.

5000 lost soles, 2018, Bali, Indonesia

The second example is of an entrepreneurial nature and feeds into the tourism industry here in Bali. While curating Mengening beach on theWest coast we collected a total of 1000discarded shoes. Within these two hours we also collected the impressive number of 21 hotel slippers.

Among others, the participants of this Curating the Beach outing were shoe designers from Indosole, a fashion brand dedicated to being “the most responsible footwear company in the world, featuring all natural,

vegan, and recycled materials.” Appalled by the ‘design failure’ of non-recyclable, non-compostable, single-use hotel slippers, the designers were

inspired to invest in a solution: an all-natural and 100% biodegradable hotel slipper. Bali caters for 5.5 million tourists per

year. Bali’s economy does not include an efficient waste management system. Everything that is not used anymore is either burnt by the side of the road or thrown into the gutter from where it gets washed into the ocean. Ironically Bali makes money with the beauty of its beaches. From an environmental point of view it is ignorant to sell tourists products that pollute the very beaches they want to enjoy. In this environment, only biodegradability makes sense.

Everything changes but nothing is lost. This is how nature works and humans, as part of the big whole, cannot escape this law of nature.

Picking up litter on beaches I am constantly in touch with nature and thehuman leftovers therein. What I touch, touches me—that moment not only my hands connect, all of my senses and my heart are being touched. Being in nature I become like a child again: open, sensitive, innocent. The guard of criticismdrops and waste simply becomes colour within a landscape, pollution becomes anopen possibility.

My personal liberation from the burden of being ‘the polluter,’ of being part of the Anthropocene, is my deep connectionwith nature. It is this that I pass on toothers by bringing them out into thewild. Everything else follows naturally from this connection with nature: awareness, responsibility and action—andlast but not least, art.

Visit liina klauss’ website here.

She also was just featured in a Hong Kong newspaper. See here.

Stay tuned for more Weekly Excerpts.